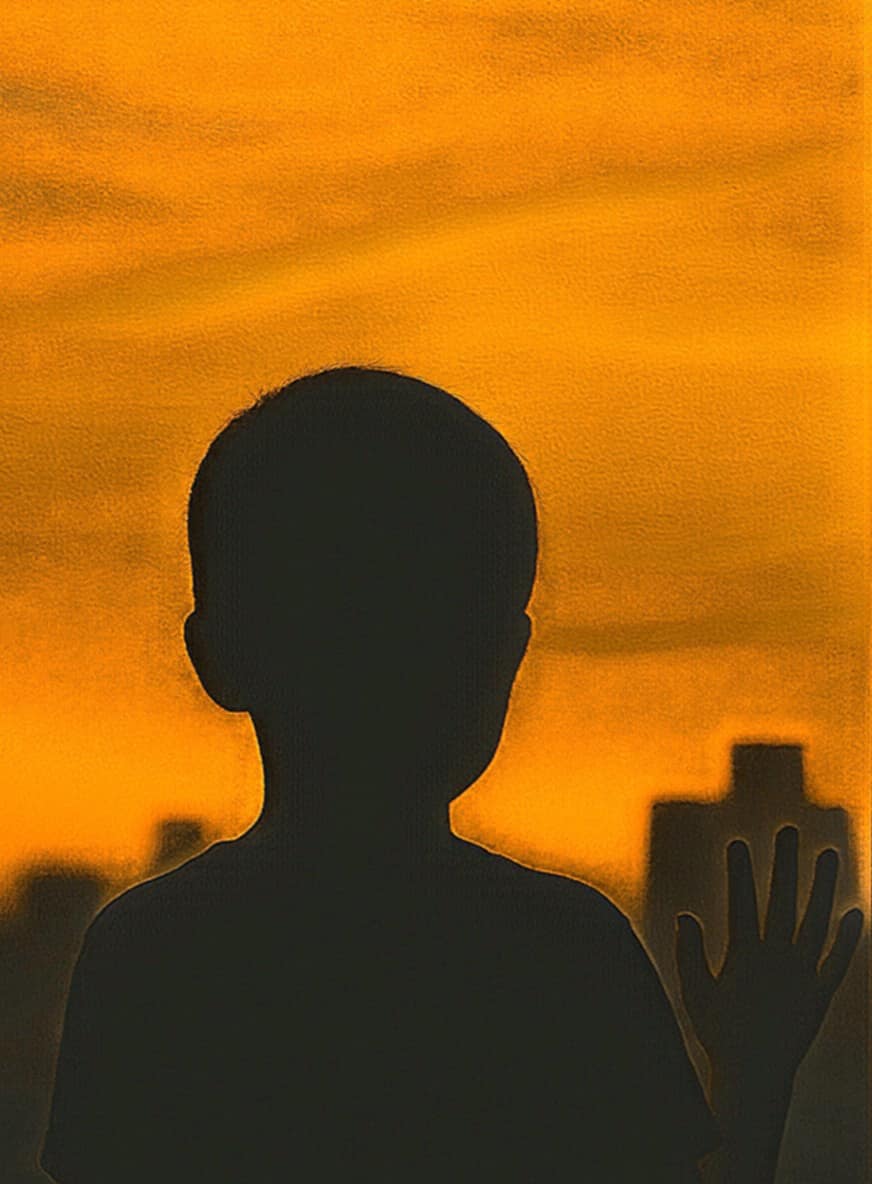

Imagine a boy born in the quiet years that followed a global war, a time when the country was rebuilding itself with confidence and certainty. A childhood spent in a quiet, upper class neighborhood inside one of the largest cities in the country would have shaped him long before he understood the world he lived in. The homes would have been large, the lawns trimmed, the streets quiet, and the people around him mostly reflections of his own family. He would have seen the best of everything because the worst would have been kept far away from him. Comfort would likely have felt less like privilege and more like the natural order of things.

His father might have been a successful real estate developer, the kind of man whose work shaped entire blocks of the city. A boy in that position would have accompanied him to construction sites and offices, watching deals unfold with a confidence that seemed effortless. In that era, the rules of real estate were clear and rarely questioned. Neighborhoods were divided by race and class. Tenants were screened according to unwritten boundaries that everyone in that world understood. A child raised in that environment would have absorbed those boundaries without ever being told they existed. He would have learned early that success meant control, and control meant never apologizing.

His mother would likely have offered a different kind of presence, quieter and more distant. She might have come from a more religious background and spent long periods managing her own health, which would mean that much of the household’s daily rhythm was carried by the staff who kept everything running. Whatever influence she might have had would have been overshadowed by the larger forces shaping his upbringing, which were rooted far more in his father’s world than in hers.

A boy raised in that environment would have seen Black people and other marginalized groups mostly in the narrow roles that world allowed them to occupy. They would have been the doormen, the drivers, the maids, the porters, the workers who kept the buildings running. They would have smiled when he walked into the room because they had to. He would not have been exposed to what happened when they went home. He would not have seen the exhaustion or frustration that lived outside the spaces he moved through. He would have seen the performance of politeness and could easily have mistaken it for contentment.

On the rare occasions he encountered someone who was not smiling, he would have had no reason to think much of it. When your own life feels effortless, you assume effortlessness is the natural state of things. Anything outside that rhythm barely registers. A child raised in that kind of comfort would not question why some people struggle. He would simply grow up believing that ease is the baseline and that anything less means something has gone wrong.

And if he ever encountered someone who wasn’t smiling, someone with a grievance or someone who felt wronged by his father, he would have seen only the surface of that moment. He would have watched his father respond with the kind of practiced toughness that adults in his world admired, never realizing that the anger directed at his father might have been earned. To a boy raised in that environment, confrontation would have looked like proof of his father’s strength rather than evidence of the harm his father could cause.

His schooling would likely have reinforced the hierarchy. He might have attended private schools and later a military academy, environments where discipline, order, and authority were not just values but daily realities. The student body would have been overwhelmingly white. The expectations rigid. The message unmistakable. The world was divided into leaders and followers, winners and losers, people who gave orders and people who took them. A boy in that setting would have learned to admire strength, distrust softness, and see vulnerability as a liability.

He would have grown up in a post World War Two America obsessed with strength. The headlines of his childhood would have been filled with the aftermath of the war and the rise of the Cold War. Adults around him would have talked about dictators, invasions, nuclear threats, and the need for powerful men to keep the world in order. He would not have understood the politics. He would have understood the tone. The world was dangerous, and only strong men kept it from falling apart.

The city itself would have taught him the rest. It was booming, but it was also divided. Wealthy white neighborhoods like his would have been insulated and orderly. Poorer neighborhoods, often Black, immigrant, or working class, would have been spoken about with caution or disdain. He would not have understood why the world was arranged that way. He would only have known that it was. And when you grow up inside a hierarchy that feels natural, you assume it is.

Money would have made everything look clean. It would have covered the cracks, softened the edges, and made the hierarchy feel inevitable. The wealthier the family, the more invisible the labor would have become. The more invisible the labor, the more natural the hierarchy would have felt. A boy raised in that environment would have grown up believing that life was supposed to look effortless, that the world was supposed to bend toward him, that the dirt other people dealt with simply did not exist.

He might have been given what was called a small loan in his family, an amount so large that the people who kept his childhood running could not have earned it even if they had worked for his family their entire lives. In his world, that kind of advantage was not seen as nepotism. It was simply considered normal.

He would have learned to see his privilege as the norm.

He would have seen his insulation as simply the way things worked.

He would have taken the absence of struggle as proof that life was fair — all of it quietly shaping the worldview he carried forward.

Inevitably, he would grow up expecting to inherit not just a business but the world. A world where the hierarchy was clear, where people like him were centered, where authority flowed in one direction, and where the rules were familiar and predictable. A world where he never had to adapt because everyone and everything else adapted to him.

But as he grew older, the world he stepped into would have begun to change in ways he had never been prepared for. The civil rights movement would have challenged the boundaries he had grown up assuming were permanent. Laws shifted. Expectations shifted. People who had once been invisible in his childhood landscape were now demanding rights, recognition, and space. The smoothness he had taken for granted would no longer have been guaranteed.

For someone raised to believe that ease was the natural order of things, these changes could easily have felt like disruptions rather than progress. The world he entered as a young adult would not have matched the world he remembered from childhood. The rules were different. The tone was different. The certainty he had inherited would no longer have aligned with the society forming around him.

A person raised in lifelong comfort often assumes that their own ease is the baseline, and that any shift away from it is a sign that something has gone wrong. When society expands its definition of who belongs, who deserves rights, and who has a claim to public space, someone shaped by his upbringing could easily experience that expansion as a kind of personal diminishment. It would not be that he was being pushed down. It would be that others were finally being allowed to stand on level ground. But to someone raised to see their own position as the default, equality can feel like loss. Progress can feel like erosion. The rise of others can feel like a demand to shrink.

And once that interpretation takes hold, every social movement, every call for justice, every shift in public expectation can look like an attack on the world he believed he was meant to inherit.

He would have carried a nostalgia for a country that had never existed the way he remembered it. To him, the past would have seemed orderly, prosperous, and fair because he would only ever have seen the polished surface. He would not have seen the people who were excluded from that prosperity. He would not have seen the workers who held up the world he walked through. He would not have seen the families pushed out of neighborhoods his father built. He would not have seen the women whose choices were limited, or the people of color whose opportunities were denied, or the communities that bore the cost of the comfort he took for granted.

So when someone shaped by that world speaks of making a country great again, it is rarely a vision of the future. It is a reach toward a past that felt perfect only because they never looked at the people who went without so they could have more. Whether that was a choice or simply the way they were taught to see the world is uncertain, but their present convictions are built on that selective memory.

If you understand the world that he came from, maybe you can see how what followed was predictable. Not admirable, not defensible, but structurally understandable. A person shaped by that environment would not be trying to invent a new vision of the country. They would be reaching backward, toward the version of America that felt stable and comprehensible to them, the version they experienced as a child before the world expanded beyond the boundaries they were taught to trust.

This is a story about what happens when someone is raised inside a bubble built to protect them from the consequences of the world outside it. A place where assumptions harden into certainty, where hierarchy feels like nature, and where comfort becomes the baseline against which all change is measured. Seen through those eyes, the pattern is not mysterious at all. It is simply the predictable outcome of the world that would have shaped them.

Leave a Reply