America is not a city of stone and steel, it is a stage. The skyline is a painted backdrop, the streets are plywood facades propped up to look solid. What seems permanent is only performance, a set designed to convince us of its reality. And just as we build the scenery, we also cast the characters who walk across it.

The cast has never been fixed. For decades we have added new faces and quietly retired others, swapping one archetype for the next as if changing scenery between acts. It has never mattered whether they were real people or scripted characters, what mattered was that they stood in the spotlight, shaping how we saw ourselves. Our society has chosen again and again to elevate figures from our media, the ones who seemed to capture something essential about the moment.

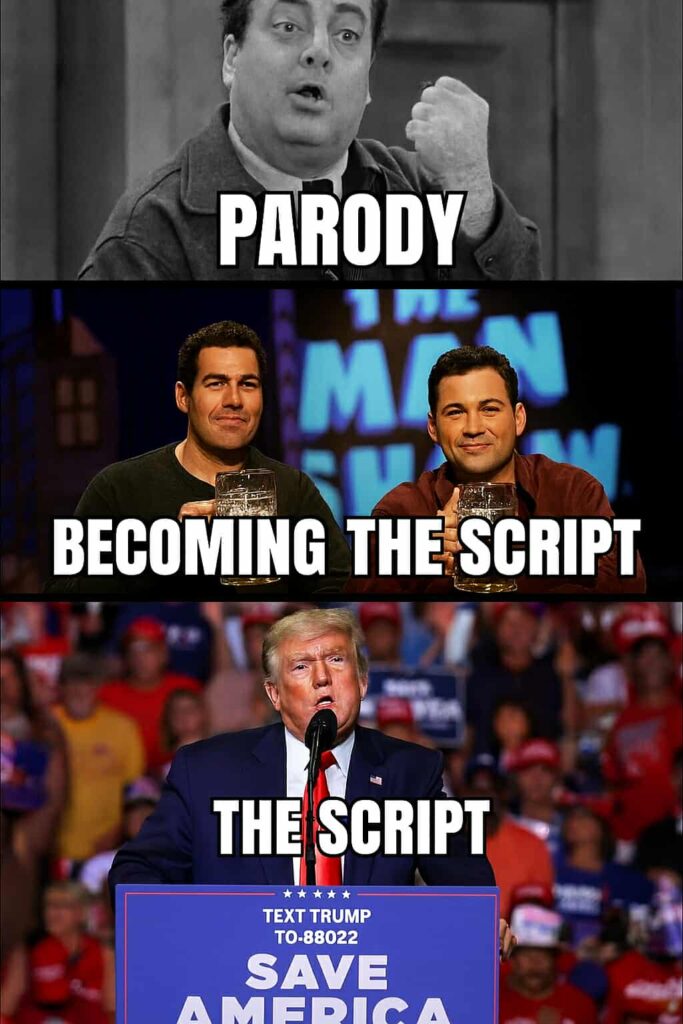

The 1950s gave us Ralph Kramden in The Honeymooners, often called one of television’s first successful sitcoms. He was a bus driver with big schemes and bigger bluster, forever threatening Alice with his catchphrase, “One of these days… bang, zoom, straight to the moon.” The line was meant as absurd exaggeration, a joke at his expense. But even then, some repeated it without irony, planting the first seeds of misreading.

The 1960s softened the patriarch without removing his authority. Sitcom husbands like Darrin Stephens in Bewitched were constantly flustered, often the butt of the joke, and clearly outmatched by the women around them. Yet the structure of the show still deferred to him as the head of the household. Samantha could bend reality with a twitch of her nose, but she usually let Darrin cling to the illusion that he was in charge. That tension, bumbling yet controlling, foolish yet still framed as the authority, became the decade’s defining archetype.

The 1970s gave us Archie Bunker in All in the Family, the most famous sitcom dad in America. He was written as a satire of prejudice, a mirror held up to the country’s ugliest instincts. The intent was clear, the audience was supposed to laugh at him, not with him. But many did the opposite. His bigotry was embraced as authenticity, his bluster as truth. The show was the number one program in the country, which meant his misreading carried enormous cultural weight. The mask slipped, and the caricature began to look like a model.

Audiences didn’t start misreading satire all at once. The ground shifted slowly. In the early television era, a character like Archie Bunker arrived inside a shared frame, three networks, a handful of critics, and a sense that everyone was watching the same thing at the same time. As syndication and reruns spread, shows could be caught out of sequence, divorced from the arcs that gave them meaning. Talk radio and cable news then built audiences around grievance, rewarding bluntness over irony. Without the conversations that once named the difference, the performance began to feel less like parody and more like truth.

By the late 1980s, Al Bundy in Married with Children embodied bitterness and resentment as comedy. He was a shoe salesman defined by disappointment, cruelty, and disdain. The writers exaggerated his failures to lampoon the hollow promise of the American dream, but audiences did not always take it that way. Quoting Bundy became a way of inhabiting him, his sneers and insults repeated not as parody but as punchlines in their own right. What was meant as a grotesque caricature of masculinity hardened into a model of it.

On the radio, Howard Stern blurred the line even further. Unlike Bundy or Bunker, he was not a character, he was himself. His crude humor, sexual spectacle, and relentless humiliation of guests were presented as authentic, not scripted. That authenticity was the hook: listeners felt they were hearing the “real” man behind the mic. But the very lack of a mask made the satire impossible to separate from sincerity. What had once been parody now sounded like permission, and Stern’s format of longform riffing, outrageous stunts, and a clubhouse atmosphere became legendary, a style many would later try to recreate.

Television carried that sensibility forward with The Man Show, created by Adam Carolla and Jimmy Kimmel. Its beer‑chugging, frat‑house energy and “Girls on Trampolines” became shorthand for the whole enterprise. It was billed as comedy, but rarely signaled how it should be read. For many, it felt less like parody and more like celebration. Instead of challenging the behavior it exaggerated, it normalized it. Looking back, the format feels like a prototype for the influencer podcasts that dominate today, two men performing as themselves, blurring humor with grievance, packaging entertainment as lifestyle.

By the time Stern’s format and The Man Show’s sensibility collided with the early internet, the ground had shifted again. Clips and catchphrases no longer lived inside the shows that gave them context, they circulated on their own, detached from the wink that once signaled parody. A joke could be replayed endlessly, stripped of irony until it sounded like sincerity. As social platforms grew, algorithms accelerated the process, rewarding outrage and affirmation over nuance. What had once been satire became raw material for identity, consumed not as commentary but as instruction.

Reality television then erased the last traces of irony. Shows like The Real World, Survivor, and Jersey Shore presented exaggerated behavior as real life. Aggression and dominance were no longer fictional caricatures but performances by actual people.

Social media amplified the pattern. Influencers built entire identities around grievance and exaggerated masculinity, packaging performance as lifestyle. Algorithms stripped away context, turning thirty‑second clips into philosophy. What was once a parody was now sold as truth.

Trump understood this better than anyone. He used social media not just as a megaphone but as a stage, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and performing directly for an audience that rewarded spectacle. In doing so, he blurred the line between entertainment and politics until they became the same act. Social media and politics had merged, and the performance of grievance became a campaign in itself.

Politics followed the same script. The presidency itself became theater, measured not by policy but by applause. Donald Trump embodied the facade without nuance. Raised in affluence, shielded from struggle, he performed wealth and dominance as if they were character. His obsession with appearances was constant. At military parades and gatherings, he fixated not on strategy or sacrifice but on how things looked: uniforms, body types, grooming. His ally Pete Hegseth even echoed this, telling generals there should be no more beards and no fat men in uniform, as if the strength of the military could be reduced to a dress code. For Trump, presence mattered more than substance, and looking the part was treated as the same as being the part.

That same fixation extended beyond politics into the spaces he built. Even in the White House, he pushed for a massive golden ballroom, a monument not to governance but to spectacle. The project, lavish and gilded, was less about function than about leaving behind a stage set stamped with his image. Just as he measured generals by their grooming and parades by their optics, he measured legacy by how it glittered.

The obsession with appearances also shaped how he spoke about the nation itself. After deploying the National Guard in Washington, D.C., he praised the city for being “so clean.” But the cleanliness was an illusion. The streets were empty because people had been driven away. It was the same logic he applied everywhere: optics mattered more than reality, and the absence of life was mistaken for order.

With Trump, the set itself became the stage of politics. The performance was mistaken for the substance. That is what happens when nuance disappears, when we forget how to tell the difference between character and truth.

Nuance is what lets us enjoy a character without imitating him, recognize performance rather than prophet, see exaggeration without mistaking it for instruction. Without nuance, satire hardens into scripture, parody into personality, and appearances into reality. Without nuance, we live inside the facade.

It was never just Al Bundy or Howard Stern or even Trump himself. The deeper problem is that we stopped having the conversations around them. We no longer allow space to say what was parody and what was poison, what was worth laughing at and what was worth rejecting. Without those conversations, the artifact becomes the only experience people have with the idea. And when the artifact is all you have, you start to assume that anyone who likes it must be like you. That is how fandom hardens into cult, and how cult becomes mob. It turns into “you’re either with us or against us,” as if every symbol demands total allegiance. But life is not that simple, and it never was.

The danger is clear. A society that lives only in facades eventually collapses when the set can no longer hold. But the hope is also clear. If we relearn nuance, if we teach how to interpret, how to question, how to see the scaffolding behind the set, we can rebuild something real behind the stage. That work does not have to be abstract. It can look like a classroom where Archie Bunker is taught as satire, not scripture. It can look like a family pausing a sitcom to talk about what is funny and what is toxic. It can look like a feed where context is restored, not stripped away.

America does not need to remain a hollow movie set, all facades and lifeless backdrops. It can be more than scenery. Our task now is to build something authentic behind the stage, a place that can hold us, shelter us, and protect us when the painted walls fall away.

Leave a Reply